France

Rèpublique Française

Aircraft Industry Nationalization

1936 - 1937

FranceRèpublique Française Aircraft Industry Nationalization1936 - 1937 |

|

After a series of widespread, nationwide labor strikes in 1936, approximately 80% of the existing French aircraft industry was nationalized and combined into seven "Société Nationales" (National Companies). Many aviation references that deal with French aircraft companies of this time period only mention this in passing. This document will attempt to provide some more detailed information about the circumstances that led up to this situation, as well as the companies, organizations and people involved.

In part due to a perceived crisis in the French aircraft industry, in September 1928 a Ministère de l'Air was created. Three methods were proposed to resolve the crisis:

To encourage technical innovation, aircraft research was given the highest priority. A new prototype policy was implemented:

As a result of this program, over 200 contracts were awarded. This resulted in far too many aircraft to actually produce, resulting in waste. Further, these contracts were paid in three installments, which resulted in some companies simply abandoning projects after receiving their initial payments. Some positive results did occur, including all-metal aircraft construction and increased aircraft speeds.

The French aircraft industry was primarily located in and around Paris, due to "... the availability of engineers, draftsmen, and skilled workers, and proximity to the ministries..."[5] This resulted in the majority of aircraft factories being susceptible to attack in the event of another war. As encouragement for aircraft companies to relocate further away from Paris in various provinces, in 1928 the Ministère de l'Air "...established a fund to subsidize the costs of starting or enlarging provincial plants." [5] A few new factories were built as a result of this program:

However, many aircraft manufacturers were still located in or around Paris, as were all of the aircraft engine firms. Further, many aircraft factory workers were not interested in relocating from the Paris area to the provinces.

It was thought that there were too many aircraft manufacturers, and in 1929 - 1930 the Ministère de l'Air decided to work with the Chambre Syndicale des Industries Aéronautique, an industry group that represented aircraft, engine and equipment manufacturers. It was hoped that the CSIA would "...form groupements, or company groups, that would pull firms together into trusts and lay the foundation for future mergers."[5] Two groupements were created:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Only two company mergers resulted: Loire-Nieuport (1935) and Potez-CAMS (1932). Further, the CSIA "...created a liquidation fund, financed through the groups, to compensate weak firms that might otherwise fall into bankruptcy. In short, the builders used the company groups not to rationalize the industry by closing down plants and negotiating mergers but rather to protect themselves from the very process of concentration..."[5]

With the failure of the two groupements, the Ministère de l'Aire proposed a new plan in July 1934 to the Chambre Syndicale, which "...called for accelerating the drive to locate factories in the provinces, adopt modern machinery, and consolidate the airframe sector into five or six firms."[5] Six new groupements were created. It is unclear which companies were involved, other than one groupement consisting of Potez, Bloch and C.A.M.S. and one groupement consisting of Farman, Mureaux and Blériot. As well, at least eight companies refused to join a groupement. As before, the companies involved used the groupements to their own benefit: "Each group created a central bureau to parcel out orders to member firms, negotiate contracts, and search for foreign clients." [5]

For various political and social reasons outside the scope of this document, in April - May 1936 the left-wing Front Populaire political alliance won the French legislative elections, gaining control of the French government. At the same time, worker's trade unions were regaining power. On 1 May (May Day, and also International Worker's Day), there were various demonstrations and marches by trade unions.

Nationally, the May Day mobilization proved particularly effective in metalworking and aviation; in the Paris region alone more than one hundred thousand metalworkers stayed away from work that day, and for the first time in fifteen years the Renault plant had to close for lack of workers. At Bréguet's Le Havre plant a remarkable 90 percent of the work force failed to show up for work.[5]

The following week, on 9 May, the director of the Breguet factory in Le Havre fired two militant workers, allegedly in retaliation. In response, 500 factory workers initiated a sit-down strike on 11 - 12 May. While the situation in Le Havre was eventually resolved, this touched off widespread sit-down strikes in the French aircraft industry through the rest of May 1936, continuing into the beginning of June. The strikes spread into various other French industries, resulting in over 1,000,000 workers throughout the country on strike; they demanded increased wages, reduced work hours, the establishment of shop steward systems and recognition of worker's rights to join trade unions. Meetings were held between the French government, various trade union organizations and industry trade groups. On 7 June, the Matignon Accords were signed by the French government and the leading trade union organizations, which acknowledged the striking worker's demands. Later in June, the French Assembly passed legislation that enacted these changes, including two weeks of paid vacation and a 40 hour work week.

One of the main tenents of the Front Populaire was nationalization of the French armament industry, in part to remove the incentive for perceived war profiteering. Given the failure of the previous attempts to resolve the various issues with the French aircraft industry, nationalization was also seen as a potential fix.

Private employers had failed to streamline the industry and modernize production or even to keep up with the modest ambitions of Plan I. The system of groupements had become thoroughly discredited as a form of industrial concentration. Little had been done to alter the habits of overpricing and uncompetitive contracting that government inspectors had exposed years before.[5]

Along with other intitiatives, like re-structuring the Armée de l'Air and developing plans to acquire larger numbers of modern aircraft, the Ministère de l'Aire proposed nationalization of the aircraft industry. Legislation authorizing nationalization of not just the aircraft industry, but the entire French armament industry, was passed by the French Assembly in August 1936, with the requirement that it be completed by 31 March 1937, as well as setting a budgetary limit on total expenditures. The Naval Ministry only opted to nationalize two small companies, and the War Ministry nationalized nine munitions companies as government-run state arsenals. In contrast, 80% of the French aircraft industry was nationalized during the period from November 1936 - April 1937.

Using its limited budget of 270 million francs, the Ministère de l'Air (along with the Finance Ministry) acquired a controlling interest (2/3 of the shares) of each company to be nationalized, then re-organized them into five regional groups as Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques (SNCA, or National Aeronautic Construction Companies):

|

Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques de l'Ouest Est. 16 November 1936 Chief Administrator: Marius Olive |

||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) | Research Facilities |

| Breguet | Nantes-Bouguenais | Private |

| Loire-Nieuport | St. Nazaire, Issy-les-Moulineaux | Nationalized? |

|

Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques du Sud-Ouest Est. 16 November 1936 Chief Administrator: Marcel Bloch |

||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) | Research Facilities |

| Blériot | Suresnes | Private |

| Bloch | Villacoublay, Courbevoie, Châteauroux-Déols | Potez-Bloch Agreement |

| Lioré et Olivier | Rochefort | Nationalized? |

| SASO | Bordeaux-Mérignac | Nationalized? |

| SAB | Bordeaux-Bacalan | Nationalized? |

| UCA | Bordeaux-Bègles | Nationalized? |

|

Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques du Sud-Est Est. 21 December 1936 - 1 February 1937 Chief Administrator: Louis Aréne |

||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) | Research Facilities |

| C.A.M.S. | Vitrolles | Nationalized? |

| Lioré et Olivier | Clichy, Argenteuil | Nationalized? |

| Potez | Berre-l'Étang | Potez-Bloch Agreement |

| Romano | Cannes | Nationalized? |

| SPCA | Marseille | Private? |

|

Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques du Centre Est. March 1937 Chief Administrator: Outhenin-Chalandre |

||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) | Research Facilities |

| Farman | Boulogne-Billancourt | Nationalized? |

| Hanriot | Bourges | Nationalized? |

|

Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques du Nord Est. April 1937 Chief Administrator: Henry Potez |

||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) | Research Facilities |

| Amiot-S.E.C.M. | Caudebec-en-Caux | Private |

| A.N.F.-Mureaux | Les Mureaux | Nationalized? |

| Breguet | Le Havre | Nationalized? |

| Potez-C.A.M.S. | Sartrouville, Méaulte | Potez-Bloch Agreement (assumed) |

In Toulouse, there were two aircraft companies: Avions Dewoitine and SIA Latécoère. Dewoitine was nearly bankrupt, and Pierre-Georges Latécoère refused to let his company become nationalized. In September 1936, workers at the Dewoitine factory petitioned the government to create a sixth SNCA to save their company, and to include Latécoère as well. Ultimately it was decided to nationalize Dewoitine as SNCA du Midi, with Latécoère remaining private. However, Latécoère workers were given the right to transfer to the new SNCA, which 549 out of 807 did.

|

Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques du Midi Est. September 1936 - April 1937 Chief Administrator: Émile Dewoitine |

||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) | Research Facilities |

| Dewoitine | Toulouse | Nationalized? |

In addition to nationalizing the above aircraft manufacturers, in 1936 the Breguet factory in Villacoublay was taken over as a state-run arsenal.

|

Arsenal de l' Aéronautique Est. August 1936 Chief Administrator: Michel Vernisse |

|

|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) |

| Breguet | Villacoublay |

With few funds left, in April 1937 the Lorraine aircraft engine factory in Argenteuil was nationalized as SNC de Moteurs. Minority shares were acquired in the two largest French aircraft engine manufacturers: Gnome et Rhône and Hispano-Suiza.

|

Société Nationale de Construction de Moteurs Est. April 1937 Chief Administrator: Claude Bonnier |

|

|---|---|

| Company | Location(s) |

| Lorraine | Argenteuil |

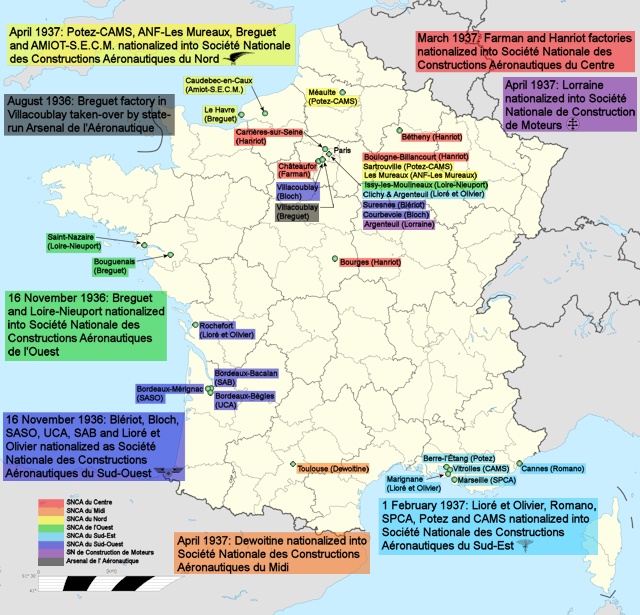

Map of France showing Société Nationale factory locations (click to enlarge)

Base Map Source

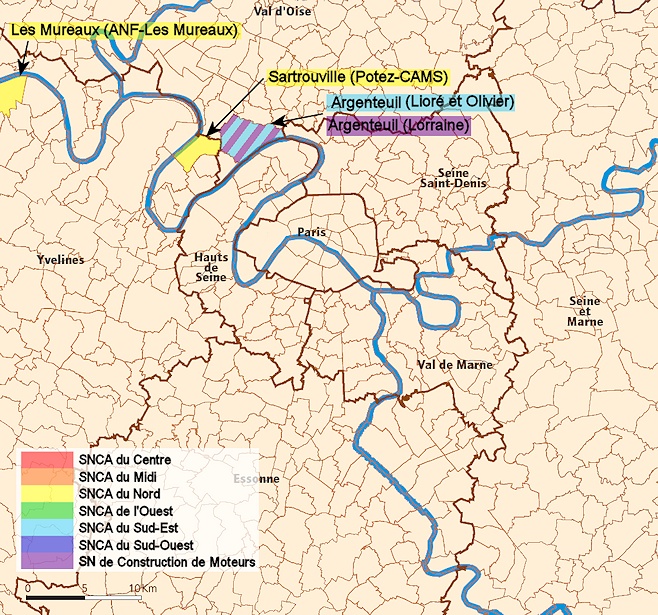

Map of Paris suburbs showing Société Nationale factory locations (click to enlarge) Base Map Source |

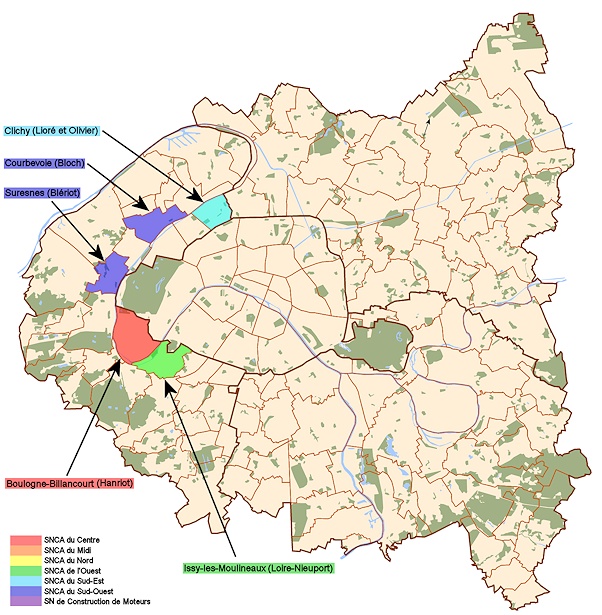

Map of Paris and its inner ring départements showing Société Nationale factory locations (click to enlarge) Base Map Source |

A chief administrator was appointed to run each Société Nationale:

Henry de l'Escaille, the head of the Chambre Syndicale, was appointed as president of the entire SNCA group.

Many of the aircraft manufacturers had research facilities. The owners were provided with three choices for these upon nationalization:

The followng aircraft manufacturers remained independent:

With the exception of Lorraine (as noted above), all French aircraft engine manufacturers remained indepenent, including Clêrget, Farman (aircraft engine division), Gnome et Rhône, Hispano-Suiza, Potez (aircraft engine division), Renault (aircraft engine division) and Salmson (aircraft engine division). As noted above, minority shares were acquired in Gnome et Rhône and Hispano-Suiza.

In addition to the nationalizations, three new national agencies were established:

After the invasion and partial occupation of France by Germany, futher industry consolidation occured:

After World War II, industry consolidation and nationalization continued:

| Sources |

| Web Links |

| [ | France | ] |

| [ | Home | | | About | | | Contact | | | Top | ] |

© 1997-2017, Robert Beechy

http://fire.prohosting.com/uncommon/reference/france/nationalization.html

Originally posted 27 December 2017

Modified: 12/27/2017